On the urgency of preserving digital documentation

Reflections on the gathering of the Network for Empowerment, Solidarity, and Transregionality (NEST) in light on recent attacks on activism and archives.

On November 6 and 7, 2024, The Feminist Institute and 19 other transnational, independent art organizations working at the intersection of feminism and art converged in Paris for the first gathering of the Network for Empowerment, Solidarity, and Transregionality (NEST).

Initiated by AWARE: Archives of Women Artists, Research & Exhibitions, NEST is based on mutual support and learning, the exchange of feminist practices and methodologies, and aims to explore pressing questions surrounding structural issues such as funding and sustainability as well as resistance in hostile political contexts. This gathering opened with a closed door session on November 6 and concluded with A Story Called Joy at the Palais de Tokyo on November 7.

The gathering was exhilarating. It was powerful to hear about the critical work happening at the intersection of feminism and art around the world. Unmistakably, for those organizations coming from the United States, this gathering coincided with our country’s presidential election. Waking up to the result on November 6 before heading to the closed-door session to discuss feminist organizing and archival practice was heavy and surreal.

The full reality of what has since come for activism and archives since the beginning of the year had not quite been realized in the hours and days after the election. Instinctually, as we met and discussed our shared struggles, it was evident that it is more pressing than ever to proactively document and preserve feminist digital documentation, as done through our partnerships and, in particular, our Preserving the Feminist Internet program.

At A Story Called Joy, I was asked to respond to a question about everyday urgency and its relationship with time and archival actions. Below you will find an excerpt from this talk with accompanying images. In light of recent attacks on education and information work, this everyday urgency has shifted into an immediate emergency. As websites and other digital information are actively removed from public view and destroyed, preserving digital documentation is even more urgent and critical.

We encourage you to advocate for the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), especially in light of recent actions which have placed the agency’s staff on administrative leave and the future of awarded grants uncertain. We also encourage you to review key resources from mission-aligned organizations, such as OpenArchive and WITNESS, to securely document any abuses of power. You can also review the critical work of the End of Term Web Archive team to monitor how government websites have changed since the beginning of the year.

Primary source documentation is more critical than ever. We hope you’ll join us as we fight to accurately preserve this moment in history.

How does our everyday urgency relate to time? How do you find persistence in time with archival acts or matters?

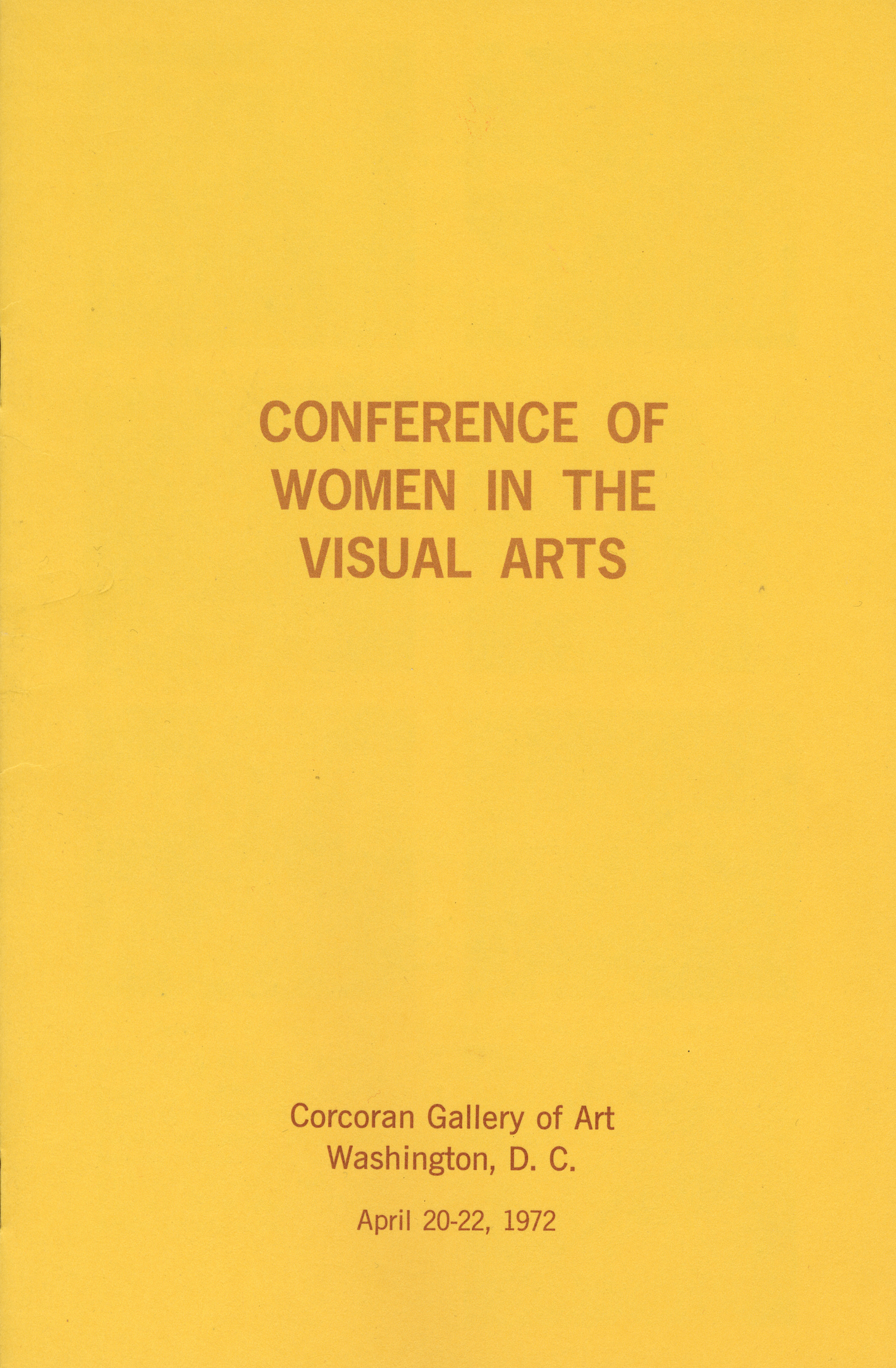

It’s important to place persistence, urgency, and time within the context and history of feminist gatherings and networks such as NEST. Pictured here is a pamphlet from the Conference on Women in the Visual Arts, held from April 20 to 22, 1972.

Co-organized by artists Mary Beth Edelson, Josephine Withers, Barbara Frank, Yvonne Wulf, Cynthia Bickley-Green, Susan Sollins, and Enid Sanford, the event was held at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and was seen as a national forum to create connections, exchange ideas, and to promote further engagement among the participants and beyond.

In her post-conference write-up, Edelson discussed leaderless and fluid sessions that took hours to decide the simplest of things. She noted that the urgency and profundity of the moment stood in direct opposition with the brief amount of time they had, stating “perhaps there is never time to [exchange ideas] at leisure with individuals from around the country. Perhaps … it was only wishful thinking on our part. But when [it was all over] we wanted to carry on … and it was too late. I sensed that many felt this way–when it was time to end we were just beginning.”

We are lucky to have this booklet and Edelson’s postmortem thanks to the primary source documentation from the planning of this event that Edelson saved. The Feminist Institute worked to preserve her studio archive in 2018. As a result of this work, selected materials are available publicly on our website and the physical documentation lives at Fales Library at New York University.

As such, as I thought about the nature of the question, it brought me back to Edelson’s quote about time. Archivists are often not afforded the luxury of time, even in well-funded institutional settings. Most of Edelson’s records were analog and stored in impeccably organized file cabinets. However, she had boxes of deteriorating audiovisual materials, of which the most recent formats that were shot in the early to mid-2000s were in the worst condition. She also left multiple hard drives that were no longer usable or readable in the state in which they were left.

Documents and printed photographs if left in a shoebox in normal environmental conditions can last for generations. Working with analog materials in that sense has a certain passive persistence. But I worry about the digital documentation developed by feminist artists and activist groups and how their work and struggles could be lost not only to time but to misinformation, cyber attacks, and rapidly shifting technology.

Archivists are information activists who aim to make sure that people’s efforts and stories persist in the face of multiple forms of opposition and resistance to truth telling. I am one person amongst a series of people before and after me who aim to ensure that information is freely available. That said, ensuring persistence with digital documentation is a trust exercise in which we hope that the next generation will continue documenting and maintaining these critical primary source materials. In the face of this uncertain persistence, leaning into that trust is an inherently feminist act.